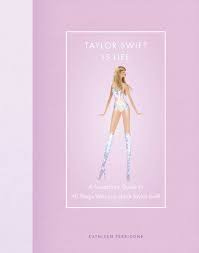

I was sent a review copy of Kathleen Perricone’s new book Taylor Swift is Life: A Superfan’s Guide to All Things We Love about Taylor Swift. I was very curious to read a new book on Swift, given that I’m writing my own (very different) one. And I had a good time with it, with a few caveats.

The book’s subtitle presents it as the work of a “superfan” for other superfans. Although a true Swift superfan will find little new information here, the book is a very readable “guide” through, first, an overview of Swift’s biography, then her discography, and the more nebulous but perhaps more interesting category of “Swiftology,” a smattering of different facts and observations about her work. (Perricone has written books with variations of the same title about other musical artists including Beyoncé and Harry Styles, which I haven’t read).

The biographical section is probably the least new; there have long been unauthorized biographies of Swift repeating the same stories she has told in interviews. But this is much better written than other Swift biographies I’ve read.

The section on the albums is a useful reference. It discusses elements such as track five of each album (typically where Swift places her most personal or important songs), cover art, and rerecordings, and notes which songs occur in different versions of each album. These sections are generally sound, although the discussion of The Tortured Poets Department betrays the problems with trying to put together a comprehensive guide to Swift’s discology. There is no mention of the double album or the songs that appear on the Anthology version. The explanation of the album is idiosyncratic, as the album is said to be about Joe Alwyn, when much of it actually turned out upon release to be, surprisingly, about Matty Healy (and on one or two occasions Travis Kelce). (For example, “The Alchemy” and “But Daddy I Love Him” are said here to be about Alwyn. I’d say - not that this kind of biographical interpretation is my usual thing - that the general consensus is that they’re about Kelce and Healy, respectively). I suspect this section to have been written before the album’s release and to be the result of guesswork that didn’t quite pay off. (Though I should say this is just my interpretation based on the available facts, and I might be wrong).

The section on “Swiftology” did contain some information I didn’t know, such as a discussion of a fan chant and its origins. It takes on a very wide range of topics, from elements that recur in Swift’s work (such as mentions of her birth month, December) to aspects of her fame (like the fan theory Kaylor). But there is very little discussion or close reading of lyrics. I suspect this might have to do with worries about the legality of quoting song lyrics, as I know this was something that came up with my book: because it’s a book of close reading, my book needs to quote Swift extensively, which required the lawyers at my agency to figure out national differences in the laws around this. I suspect this might have influenced Perricone’s, or her publisher’s, decision to mostly only cite the titles of songs when discussing lyrics.

Anyway, I had a good time reading this book. It would make a good present for a Taylor Swift fan, especially if that fan is a child. The book is short and, I believe, intended for a young audience (the packaging on the box I received from the publishing house described it as a children’s book). It’s a fun object to own; the illustrations by Adrian Valencia are charming and the pages are purple. I don’t think it’s going to convince anyone to take Swift seriously, but to be fair it’s not really trying to.

If you’re in the mood for a different kind of (tenuously) Swift-related book, I enjoyed Honey: A Novel by Isabel Banta. (It’s not really Swift-related, as it’s more of a fictionalization of the careers of slightly older artists like Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake). It’s about a young pop star in the nineties and 2000s facing a variety of career-related and interpersonal difficulties as well as a barrage of sexist press. It’s - to its credit - nowhere near as miserable as that summary makes it sound. In fact, it keeps you guessing where it’s going to end up tonally - is it about the waste of young talents, a love story, something else? - in a way I found really interesting. I read Sarah Ditum’s Toxic: Women, Fame and the Nineties earlier this year (also a really interesting book) so I knew a little bit about the media environment around famous women in this period but Honey functioned as a kind of Proustian madeleine, bringing me back to my own uncritical reading of magazines in the 2000s and the kinds of language they used and narratives they constructed about famous young women.